During the medieval period, both the Arabic and the Scholastic philosophers tackled the account of generation and that of substantial change, advancing various interpretations drawn from the texts of Aristotle. In this section, I will 1) lay out the accounts offered by Avicenna, Averroes, Aquinas and Suarez in order to better understand the philosophical background against which Sennert was competing, and then 2) raise some issues these views present with regard to the roles played by the formal causation in each case. In doing so, I will first give a short summary of Aristotle’s own account on the generation of beings, i.e. composite substances.

Aristotle argued that there are three ways in which one can speak of generation of substances: generation can be natural, artificial or spontaneous. In all three cases, he maintains, the producer and the product must be the same in form. This does not mean that the form in question must be numerically the same, but it suffices that it is the same in type, i.e. the form of parent is numerically different but the same type of form with the form the offspring will have. So for instance, in the case of the generation of a human being, the producer (the male) have the same form as the product (the offspring), but the latter shares the same form in a different piece of matter that is provided by the female. That the producer must share the same form with the product is commonly referred to as the Synonymy Principle. This principle holds in the other cases of generation, though Aristotle struggles to offer a coherent explanation. In the case of artificial generation, for instance, it is rather difficult to accept that the form in question is the same in type as spoken of in the case of natural generation. For in making a statue, a sculptor does not pass onto the matter the form as the parent passes it onto the matter through semen. Aristotle thinks, however, the principle sufficiently holds insofar as the form in the sculptor’s mind is the cause of the material realization of that form in the bronze as a statue.[1] In the case of spontaneous generation, this principle is even harder to defend, for there is no producer that realizes the product to begin with! Yet, Aristotle wants to say that the principle holds at least partially, and hence is satisfied, because the matter out of which things come to be spontaneously already contains a part of the final product.[2] In the Metaphysics, Aristotle uses an example of spontaneous recovery from illness as a type of spontaneous generation insofar as it generates health where health was previously absent.[3] For normally, health is restored by the intervention of a doctor, who plays the role of the producer of health, it so sometimes happens, says Aristotle, that the body can spontaneously warm itself up, hence bringing an equilibrium in the bodily humour, which then restores the balance disturbed. In this spontaneous recovery of health, the agent that brings about such recovery is the heat in the body. This heat in the body, therefore, is a part of the final product, i.e. health, and since the agent is a part of the final product, some sort of partial sameness also exists between the product of spontaneous recovery, i.e. health in the agent, and what produces it, i.e. heat in the body.[4] However, even in this case, such a spontaneous recovery must presuppose a pre-existing producer as a composite substance, and such “spontaneous generation” as recovery of health in the agent seems to be nothing but an accidental generation. First, because generation must be a product of a composite of form and matter, but in the case of spontaneous recovery, there is no composite of form and matter coming into being, and second, such change as recovery of health happens in an already existing composite being, i.e. substance. Whatever happens to that being internally would not make any substantial change in its being. These then are problems that are left unanswered by Aristotle, and any new account must be able to ameliorate these issues.

Nonetheless, the medieval philosophers continued on holding the Synonymy Principle as the defining feature of the account of generation, but focused on the role form plays rather than the matter, for form alone seems to be responsible for making a specific matter distinct from any other. The Aristotelians reasoned that in the generation of substances, if the producer and the product are the same in form, it must be that form is what individuates matter, directs and orients the coming into being of sensible substances. In this way, they appealed to the pre-existence of form in the producer to explain why the generated product shares the characteristics the producer has. In a way, generation is seen as a process consisting in the transmission of a form from the producer to the product.[5] Simply put, the coming into being of composite substances is nothing but acquisition of a form of a certain kind, and the role form plays in generation is equated with the role of forming the internal structure and organization of sensible objects.

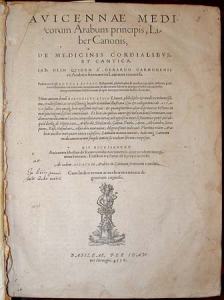

For Avicenna, substantial generation does not occur gradually, but happens all at once. Nevertheless, there are several substantial changes occurring before the seed can become an animal or a full-fledged human being. For Avicenna, substantial changes happen when sufficient amount of accidental changes, i.e. qualitative change, prepare the way for the substance to change. John McGinns gives a clear analysis of Avicenna’s generative account. Citing passages from Avicenna’s Book of Animals, McGinns explains that Avicenna conceives at least four substantial changes in the form-matter composite before an animal is generated. The initial stage involves “the churning of the semen”, which Avicenna equates it with the “actuality of the formal power”. Second, the blood clot manifests in the uterine wall; the first substantial change in the generative process. Third, this blood clot (or zygote) is replaced by yet another new substance, i.e. embryo, which leads to the generation of the heart, primary organs, blood vessels and limbs. Lastly, the animal is formed, which is yet a different substance. In this way, these changes from semen to animal take place through a series of discrete substantial changes, even though a number of gradual qualitative changes do occur, preparing the way for each discontinuous leap between substantial changes.[6] The matter, then, undergoes a substantial change only when a sufficient number of gradual accidental changes have occurred in the said matter, acquiring a new substantial form fit for the specific state of the matter. McGinns likens this process to an example of handling clay, for he says that clay is receptive at first to a number of different shapes and forms, but as soon as it is exposed to the sun, “to the degree that the Sun affects the clay and hardens it, the clay becomes less pliable and so becomes less receptive to the number of forms that the craftsman can impose upon it.”[7] The clay here is the material, i.e. menstrual blood, and the craftsman is the form, i.e. male semen. The form the craftsman imposes upon the matter is equivalent to the formative power in the male semen, i.e. efficient cause. Here, it is significant to note that, according to this analogy, Avicenna conceives of the formative power to be already in the form, that is to say, the form carries with it the power to affect the matter. This is striking in comparison with the efficient cause as an external agent, putting forth the form into the matter to work with, as it was the case with Aristotle’s account of generation. For Avicenna, clearly, the formative power, or the efficient cause, is in the form itself, i.e. semen. And this formative power gradually alters the semen qualitatively “up to the point that the seminal form is displaced and it becomes a blood clot,” continuing to develop like this “up to the point that [the developing thing] receives the form of life,” or the new substantial form.[8]

For Avicenna, substantial generation does not occur gradually, but happens all at once. Nevertheless, there are several substantial changes occurring before the seed can become an animal or a full-fledged human being. For Avicenna, substantial changes happen when sufficient amount of accidental changes, i.e. qualitative change, prepare the way for the substance to change. John McGinns gives a clear analysis of Avicenna’s generative account. Citing passages from Avicenna’s Book of Animals, McGinns explains that Avicenna conceives at least four substantial changes in the form-matter composite before an animal is generated. The initial stage involves “the churning of the semen”, which Avicenna equates it with the “actuality of the formal power”. Second, the blood clot manifests in the uterine wall; the first substantial change in the generative process. Third, this blood clot (or zygote) is replaced by yet another new substance, i.e. embryo, which leads to the generation of the heart, primary organs, blood vessels and limbs. Lastly, the animal is formed, which is yet a different substance. In this way, these changes from semen to animal take place through a series of discrete substantial changes, even though a number of gradual qualitative changes do occur, preparing the way for each discontinuous leap between substantial changes.[6] The matter, then, undergoes a substantial change only when a sufficient number of gradual accidental changes have occurred in the said matter, acquiring a new substantial form fit for the specific state of the matter. McGinns likens this process to an example of handling clay, for he says that clay is receptive at first to a number of different shapes and forms, but as soon as it is exposed to the sun, “to the degree that the Sun affects the clay and hardens it, the clay becomes less pliable and so becomes less receptive to the number of forms that the craftsman can impose upon it.”[7] The clay here is the material, i.e. menstrual blood, and the craftsman is the form, i.e. male semen. The form the craftsman imposes upon the matter is equivalent to the formative power in the male semen, i.e. efficient cause. Here, it is significant to note that, according to this analogy, Avicenna conceives of the formative power to be already in the form, that is to say, the form carries with it the power to affect the matter. This is striking in comparison with the efficient cause as an external agent, putting forth the form into the matter to work with, as it was the case with Aristotle’s account of generation. For Avicenna, clearly, the formative power, or the efficient cause, is in the form itself, i.e. semen. And this formative power gradually alters the semen qualitatively “up to the point that the seminal form is displaced and it becomes a blood clot,” continuing to develop like this “up to the point that [the developing thing] receives the form of life,” or the new substantial form.[8]

Averroes, however, takes a radically different approach to the account of substantial change in that for him, only a material agent can act upon matter and thus transform it in such a way as to produce another material being.[9] In order for there to be any substantial change, matter must be acted upon so as to be modified in order to bring about a coming into being of a composite substance. Nothing incorporeal can act upon the matter, so an agent that interacts with matter and is able to effect the required changes in matter must itself be material and possesses corporeal parts as well as active qualities.[10] Further, for Averroes, matter already contains a form that is potentially present in it, and generation is explained through the agent’s actualizing the potentiality, i.e. receptivity, for form in the matter. In other words, generation is nothing but the coinciding of such an emergence of the receptivity for form in matter with the transmission of an external form into the matter. So the agent, in transmitting the external formal principle, at the same time, extracts the receptivity for that form in matter. In this way, matter also plays somewhat an active role of accepting the new form, for if the matter remained absolutely the same with only the potentiality/passivity all through the generation, generation would just mean a production of a new form rather than the constitution of a new composite.[11] So for Averroes, matter too also undergoes transformation in the process of generation so that it is not simply a new form being imposed upon the existing material substratum but a new substance both in form and matter comes into being.[12] So in this way, Averroes fulfills the Synonymy Principle in that for him as well, both the producer and the product must possess the same form in type, but what is different from the predecessors’ account is that Averroes also takes this Synonymy Principle further and maintain that both the producer and the product have not only the form but also the material part with which the preexisting matter can be interacted. Again, this is due to his general principle that only matter can act upon matter in such a way to generate another material being, and if form does not have any corporeal part, it cannot modify the said matter at all. So whatever generates a new substance must be already be a composite of form and matter. Now, this may work well with the standard, natural generation, since forms are communicated to the matter through the seed, containing a natural power capable of transforming matter so as to bring about a full fledged individual of a certain species, but how does this work in the case of spontaneous generation where there is no prior composite being acting on the material substratum? Averroes wants to say something analogous with the natural generation happens in the cases where animal and plants are generated without seed.[13] In spontaneous generation, Averroes argues, animals and plants can come out of the matter without seed by receiving the formative power directly from the heavenly bodies, insofar as the heavenly bodies are themselves material beings.[14] This means that, even though the heavenly bodies do not have determinate bodily parts, since they operate through heat, which is a primary quality of bodies, the operation of the formative powers by the heavenly bodies still satisfy both the Synonymy Principle and Averroes’ general principle that only matter can modify matter.[15]

Although Aquinas argues also for the primacy of the composite substance of form and matter, he denies that there are forms latent in the matter, and he maintains the matter as material substratum is pure potentiality. Matter cannot pre-contain forms to be actualized afterwards, for then the form would reveal a state of actuality only of the matter, and matter would be the real subject of the form![16] Aquinas, thus, rejects both the theory of multiple hidden actual forms (latitatio formarum) in matter and the theory of inchoate forms (inchoatio formarum) that Averroes held, i.e. a theory that the acquisition of a form by matter is nothing but the bringing of the potentiality of matter into act.[17] Aquinas reasons that unless forms come to matter externally rather than emerging from within the matter, there would not be a true generation and a substantial generation, but only an accidental change in the predicate of the matter as the subject. So for him, animals as well as human beings do not pre-contain the form of an animal or of a human being, but the matter or the embryo comes to be such a state that it can acquire a fit form through changes in the matter. For the matter to come to be such a state a form of a human being, i.e. rational soul, the formative power in the semen needs to modify the matter so it forms organs suitable for living beings. Once this has been done, the matter appropriately so organized, i.e. equipped with organs, can receive a form by triggering, as it were, the actualization of the potency of the matter. This formative power is not to be confused with the soul itself, for Aquinas does not want to associate the formative power of the semen with the functionality of the souls. What the formative power does is simply organize the matter in such a way that once the soul is received, the soul can perform its functions using those organs. So the formative power is a sort of a vital operation at the moment of conception, and it is a corporeal power passed on to by the agent, which forms the matter into an organically structured stuff so it can begin to digest food if there were a soul in it. Once this digestive organs have been formed, the vegetative soul comes to be, and does its own functions of digesting, etc… The formative power, however, does not cease to be, but still keeps forming the organs to make the matter like itself, i.e. the source of itself or in this case the male semen. The formative power is indeed, what Amerini calls, “a program” for material development that “expressly tasked to structure the matter of a given body.”[18] Once the organs appropriate for sensation have been formed, the sensitive soul takes place of the vegetative soul, subsuming the powers of vegetative soul under itself. It is probably more proper to conceive of this process as transformation of an inferior soul into a superior one, an upgrade. When the organs can afford to perform more tasks, the soul too develops into a more adequate form fit for that specific matter. In this way, Aquinas avoids admitting the plurality of forms latent in the matter, yet manages to explain the various stages of biological development. Unlike Avicenna’s account, Aquinas’ account does not involve a number of distinct leaps of substantial generation in order for the semen to fully develop into an embryo, and then into an animal, but Aquinas admits a substantial generation only once at the moment of ensoulment, i.e. the union between the vegetative soul and the matter properly organized. After the vegetative soul takes its root in the matter, the soul develops into the higher soul, and throughout this entire generative process, the formative power, or the program, keeps forming the organs until it finishes its task of structuring the body.

Since Aquinas also attributes the formative power to material agent, it may be conjectured that it is some sort of vital heat that does the formation of the organs. Understood in this way, spontaneous generation is explained similarly to the account offered by Averroes that it is due to the celestial bodies providing the heat, acting upon the putrefied matter.[19]

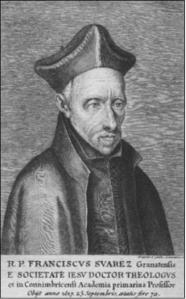

Francisco Suarez (1548-1617), on the other hand, equates rational soul with the substantial form. Aquinas avoided conflating the two (soul and substantial form) precisely because he did not want to imply that the soul, which is the efficient cause and functions with the organs, is the same as the formative power, which is merely a forming principle, i.e. its task is merely to form organs so that the soul can take on and performs its functions using the organs so organized by the formative power. It is here in Suarez that we see the Aristotle’s analogy in explaining substantial generation of artificial things and natural things starts to break apart completely. For Aristotle had argued that, in the artificial generation, the form in the sculptor’s mind is the material realization of that form in the bronze as a statue. The form in this came in the mind of the sculptor only does the formation of the material, but in forming a statue of a person, for instance, the hand so formed does not need to function as a hand. If the sculptor were to make the heart and other primary organs in making the statue, these organs either do not need to function as they would in living human body. So the formative principle, i.e. the guideline in forming a body into a specific manner, in statue-making does not involve functionality of the organs, and just as Aquinas outlines, the formative principle must be distinct from the efficient cause, which would be the sculptor in the example of the statue-making. But clearly, this cannot be the case when one is dealing with the natural generation, for in natural generation, as soon as the organs are formed, they function. In fact, even as they are being formed, they show signs of activity. It appears as though this forming principle in the case of natural generation is equipped with the active principle that is doing the forming! This point is significant, for it is true to say that the artist as the efficacious cause is necessary for the form in his mind to be expressed in the matter so as to produce an informed matter, and without the efficacious agent being present, the production halts and no further information on the matter is possible. However, with the natural generation, once the efficacious, external agent passes on to the matter a seed or semen (the corporeal matter in form that carries with it a program or structure to be actualized and realized in matter), the efficacious agent who produced such seed is no longer necessary for the rest of the formation to take place. The production, in other words, does not halt even with the absence of the external agent. The seed takes on the task of the efficacious agent at the moment of conception, as it were, and it itself performs all the functions attributed to the efficacious agent. In light of this, it is easy to see why Suarez identified the form with the rational soul. For if the forming power that also functions with the organs so formed is not the soul, what really is a soul? Is it not the case that plants are said to nurture when they are equipped with the vegetative soul? Is it not the case that animals sense and move about only in virtue of them having the sensitive soul? If so, then, it must follow that soul is that which performs all these functions attributed to the forming principle. And since the forming principle functions, i.e. is efficacious, the forming principle is not really the formal cause but an efficient cause of natural generation. Indeed, this is the path Suarez takes. For Suarez, the composite being is generated out of the matter by the efficient cause, and as a result of the matter being so organized, the new form of the composite as the substantial form of that specific composite appears. In this way, as Helen Hattab argued, the explanatory burden of accounting for natural generation and substantial change is shifted onto the efficient and material causes from the formal cause. The substantial form is now posterior to the generation of the form-matter composite, and the formal causality is reduced to a mode of the union of the substantial form to matter.[20] Since the formal causality is just a mode of union “between an already existing substantial form and an already existing matter,” it is neither the formal causality nor the material causality that performs the organic functions, but rather, it is the emergent substantial form, at least in the case of animals and plants, that is the source of efficacious causation.

Francisco Suarez (1548-1617), on the other hand, equates rational soul with the substantial form. Aquinas avoided conflating the two (soul and substantial form) precisely because he did not want to imply that the soul, which is the efficient cause and functions with the organs, is the same as the formative power, which is merely a forming principle, i.e. its task is merely to form organs so that the soul can take on and performs its functions using the organs so organized by the formative power. It is here in Suarez that we see the Aristotle’s analogy in explaining substantial generation of artificial things and natural things starts to break apart completely. For Aristotle had argued that, in the artificial generation, the form in the sculptor’s mind is the material realization of that form in the bronze as a statue. The form in this came in the mind of the sculptor only does the formation of the material, but in forming a statue of a person, for instance, the hand so formed does not need to function as a hand. If the sculptor were to make the heart and other primary organs in making the statue, these organs either do not need to function as they would in living human body. So the formative principle, i.e. the guideline in forming a body into a specific manner, in statue-making does not involve functionality of the organs, and just as Aquinas outlines, the formative principle must be distinct from the efficient cause, which would be the sculptor in the example of the statue-making. But clearly, this cannot be the case when one is dealing with the natural generation, for in natural generation, as soon as the organs are formed, they function. In fact, even as they are being formed, they show signs of activity. It appears as though this forming principle in the case of natural generation is equipped with the active principle that is doing the forming! This point is significant, for it is true to say that the artist as the efficacious cause is necessary for the form in his mind to be expressed in the matter so as to produce an informed matter, and without the efficacious agent being present, the production halts and no further information on the matter is possible. However, with the natural generation, once the efficacious, external agent passes on to the matter a seed or semen (the corporeal matter in form that carries with it a program or structure to be actualized and realized in matter), the efficacious agent who produced such seed is no longer necessary for the rest of the formation to take place. The production, in other words, does not halt even with the absence of the external agent. The seed takes on the task of the efficacious agent at the moment of conception, as it were, and it itself performs all the functions attributed to the efficacious agent. In light of this, it is easy to see why Suarez identified the form with the rational soul. For if the forming power that also functions with the organs so formed is not the soul, what really is a soul? Is it not the case that plants are said to nurture when they are equipped with the vegetative soul? Is it not the case that animals sense and move about only in virtue of them having the sensitive soul? If so, then, it must follow that soul is that which performs all these functions attributed to the forming principle. And since the forming principle functions, i.e. is efficacious, the forming principle is not really the formal cause but an efficient cause of natural generation. Indeed, this is the path Suarez takes. For Suarez, the composite being is generated out of the matter by the efficient cause, and as a result of the matter being so organized, the new form of the composite as the substantial form of that specific composite appears. In this way, as Helen Hattab argued, the explanatory burden of accounting for natural generation and substantial change is shifted onto the efficient and material causes from the formal cause. The substantial form is now posterior to the generation of the form-matter composite, and the formal causality is reduced to a mode of the union of the substantial form to matter.[20] Since the formal causality is just a mode of union “between an already existing substantial form and an already existing matter,” it is neither the formal causality nor the material causality that performs the organic functions, but rather, it is the emergent substantial form, at least in the case of animals and plants, that is the source of efficacious causation.

Suarez argues further that the human substantial form as the rational soul is essentially different from the other types of substantial forms, i.e., material substantial forms. These material substantial forms are educed out of the matter, rather than created out of nothing by God, and hence they cannot survive the material death.[21] These material substantial forms too are still united by the formal causality, i.e. the union, but because they are educed from and attached to matter, they do not properly come to be out of nothing, and what was considered as a substantial generation for Aristotle and Aquinas was reduced to the status of accidental change happening within the same subject, just like the example of Aristotle on the generation of health in a body. So for Suarez, whereas the human substantial form is created by God ex nihilo, the material substantial forms emerge out of the prime matter, and hence they do not count as a substantial generation, but only as an accidental generation.[22]

I agree with Helen Hattab that Suarez’s redefinition of the substantial form as an incomplete substance, which together with the matter makes one per se composite substance, his attribution of the efficient causality to the seed separate from the generator, and the reduction of formal causality to mode of the union of the substantial form and matter made it conceptual ground for which a new corpuscular mechanistic worldview to take roots. But I find it a little hard to believe Suarez was solely responsible for the transition from the Scholastic philosophy into the mechanical philosophy, as well as the devaluation of formal causality to the efficient causality. In fact, I believe it is somewhat too much a leap for us to come to Descartes and proclaim with him the dispensability of the formal causality after Suarez. For even Suarez utilized, in a much weakened manner, the distinction between formal causality and the other causalities. Without the formal causality, even for Suarez, it would be impossible to have the substantial form attached and united to the matter appropriate. Indeed, it would be hard to imagine why Descartes, who had had a difficulty in explaining the mind-body union could discard such a convenient cause as formal causality. In what follows, I will attempt to elucidate more in detail the general attitudes towards the use of Aristotelian causality in the beginning of the 17th century. In discussing the case of Daniel Sennert (1572-1637) and his account of causality in natural generation, I hope to show that all the groundwork for the new mechanical philosophy to take place has been laid out, and our understanding of the devaluation of formal causality, the conflation of it with the efficient causality and finally getting rid of the formal causality altogether in Descartes will be made more accessible.

[1] 1032a32-b6

[2] Gabriele Galluzzo, The Medieval Reception of Book Zeta of Aristotle’s Metaphysics: Aristotle’s Ontology and the Middle Ages – The Tradition of Met., Book Zeta, 96.

[4] Galluzzo, 98.

[5] Ibid., 182.

[6] John McGinns, Avicenna, 239.

[7] Ibid., 240-241.

[8] Ibid., 241-242.

[9] Galluzzo, 188.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid., 187.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., 198.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Fabrizio Amerini, Aquinas on the Beginning and End of Human Life, 23.

[17] Ibid., 24

[18] Ibid., 16.

[19] See Aquinas, Summa Theologiae Book I, Q45. Reply to Obj. 3, where he says “For the [spontaneous] generation of imperfect animals, a universal agent suffices, and this is to be found in the celestial power to which they are assimilated, not in species, but according to a kind of analogy. Nor is it necessary to say that their forms are created by a separate agent.”

[20] Helen Hattab, “Suarez’s Last Stand for the Substantial Form” in The Philosophy of Francisco Suarez, 101-118.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.